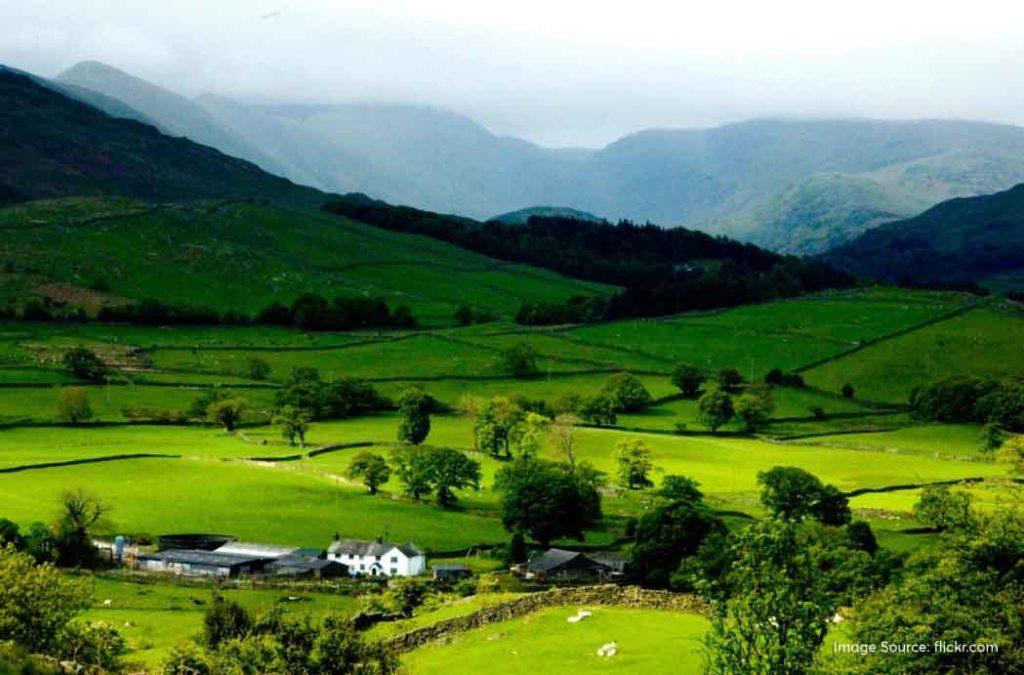

When you feel like running away from the hustle and bustle of life, head to the Ziro Valley in Arunachal Pradesh! Known for its verdant landscapes and sprawling views, this valley town encapsulates the essence of storytelling. It is because every corner narrates the tale of beauty, wonder and mystery. A place so beautiful that you tend to be engulfed in the never-ending meadows.

As you think of Ziro Valley, a lush green picture might pop into your vision. Well, that’s exactly how it looks! The pictures you see on social media apps don’t do complete justice to the awe-inspiring splendour of this hamlet. With no touristy people and high-end travel itineraries, this place is rejuvenating in the blissful nature. If you love taking strolls in a mesmerising setting, Ziro Valley is your go-to destination!

Best Places To Visit in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh

1. Tarin Fish Ponds

You must be wondering as to what is so special about fish ponds in Ziro Valley. However, this isn’t a normal place where you see fish and come back. Tarin Fish Ponds are particularly popular for their breeding techniques in high-altitude zones. You get an opportunity to learn from the authorities about fish farming.

Get ready to witness modern solutions and advancements in the area of fishing. The massively beautiful space is great for spending quiet time with your loved ones. Being one of the famous Ziro tourist places, make sure to capture the floral beauty around.

Location: GR9H+5C7, Cona County, Shannan, Arunachal Pradesh 791120

2. Talley Valley Wildlife Sanctuary

Hold your breath as you get ready to immerse in the heartwarming beauty of the Talley Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. It is one of the best places to visit in Ziro Valley for a serene atmosphere. The sanctuary is characterised by the presence of bamboo, fir and the famous rhododendron trees. The bamboo trees in the sanctuary differ from the ones found in Ziro Valley due to their location and elevation.

The wildlife sanctuary is home to a rare species known as clouded leopard. You can also spot other endangered species that can prevail in the harsh climatic conditions of the valley. It is an ideal destination to learn about biodiversity and experience natural bliss. Moreover, it also offers trekking opportunities for thrill seekers. You can always be a part of guided tours helping you navigate through the sanctuary.

Tourists love to watch the many species of floral blooms throughout the sanctuary. What makes this place a rated destination is the tranquillity that enriches your time. Imagine being amidst the woods, in complete wilderness, with no phone calls to bother you! That’s exactly the vibe of this wildlife sanctuary.

Location: HX9M+R5M, Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh 791120

3. Meghna Cave Temple

Discovered in 1962, Meghna Cave Temple is one of the best places to visit in Ziro Valley. While the exact time is not known, it is believed to be 5000 years old. That does make it an intriguing place of divine bliss! The temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva, who is worshipped in the form of Lord Lakulisha.

Located at an altitude of 300 feet, it attracts tourists from all over the country. What makes it an absolutely wonderful sight is the view from the top. Inhale the fresh oxygen clubbed with an essence of hilly areas all around. Soak in the panoramic views as you strike the right poses for Instagram-worthy pictures.

Location: 8XMQ+X44, Arunachal Pradesh 791122

Now that you are in Ziro, might as well visit Tawang for an unforgettable trip to Arunachal Pradesh. Let monasteries add more tranquillity to the journey.

4. Hapoli Market

Hapoli Market is one of the loved places to visit in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. It is a local market where you can find vegetables and fish for your delicious meals. It is also a great destination to understand the culture and everyday lifestyle of people. Make sure to negotiate the right price for the right find!

Location: Hapoli Town, Lower Subansiri District, Hapoli, Ziro – 79112

5. Kile Pakho

For the ones who get lost in the charm of the valley are the only ones who find themselves! Kile Pakho is one such amazing destination known for its awe-inspiring beauty. It is basically a viewpoint attracting trekking enthusiasts. If you love to witness the Ziro plateau, this is the place to be!

Moreover, you can also witness the snow-capped Himalayan mountains from this place. You need to trek towards the top, as it is hilly terrain. However, every step is worth watching the jaw-dropping views of the magical Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh.

6. Siikhe Lake

Siikhe Lake is one of the popular places to visit in Ziro Valley. As you visit this lake, you can witness the panoramic views of the surrounding greenery. Interestingly, it is an artificial lake made by the efforts of the state government. If you are looking for a rejuvenating time, this is the place to be.

What’s more? The lake provides a paddle-boating facility to spend a serene time on the waters. You can also opt for a motorboat if speed is what you love! Apart from this, it is a top-rated picnic spot in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. On a cloudy day, this destination looks straight like a scene from a fairytale. It is the scenic blend of blue skies and verdant landscapes that makes it a place of absolute wonder!

Location: JR8C+H6P, Siikhe Lake, Lempia, Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh 791120

7. Dolo Mando

The strategic location of Ziro offers various adventure activities for thrill seekers. Dolo Mando is one of the best places to visit in Arunachal Pradesh for an amazing trekking expedition.

It is a hilltop, located on the west side of the valley. As you reach towards the top, you can experience a blend of hues ultimately offering the right amount of solace!

Location: Daporji Road, West Side, Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh

8. Naara Aaba

While Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh, offers scenic spots, you cannot miss immersive experiences here. Naara Aaba is one of the best places to visit in Ziro for learning about wines! Yes, this winery is an iconic place that was the first to experiment with the production of Kiwi wine. What makes it an amazing destination is the story of the founder!

Tage Rita is an inspiring woman entrepreneur transcending tourism activities and making Northeast a destination for wine production. As you visit this place, you can understand the production process of wines. What’s more? Indulge in the pungent flavours of fruit wines made organically from the fruits.

Interestingly, the place was also featured on the popular TV show Shark Tank Episode 2, thereby making a global mark from this small town of Ziro. Isn’t it such a motivating tale to hear? That’s exactly why Naara Aaba cannot be missed.

Location: Village Hong, P.O/P.S Hapoli, Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh 791120

9. Tippi Orchid Research Centre

Just a few kilometres from Ziro Valley is the beautiful Tippi Orchid Research Centre. As the name suggests, it is a great place to witness the beauty of orchids. Remember, the blossoming of orchids is difficult, and it takes the right weather for them to bloom.

Even if you get to see a few orchids, you are surely lucky. The centre also has a forested area perfect for capturing pictures. It also has a greenhouse where different orchid species are well maintained for visitors to admire their beauty.

Location: Near Tippi Orchid Station Bhalukpong, Tippi Village, Arunachal Pradesh 790004

How to Reach Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh?

Airway

Tezpur Airport is a helpful airway route to reach Ziro Valley. It is located approximately 250 kilometres from the destination. You can also opt for Lilabari Airport in North Lakhimpur, which is 116 kilometres from the valley. While the latter airport has fewer flights, you can easily find flights to Tezpur from major Indian cities.

Railway

The nearest railway route is Naharlagun, which is about 89 kilometres away. You can take the Naharlagun Express from Guwahati. After reaching the railway station, you can easily hire a cab.

Roadway

You can drive or take a bus from Guwahati to Itanagar or North Lakhimpur, as these are the nearest destinations to Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. You can then hire a local taxi to reach the destination. It takes around 10 to 13 hours from Guwahati.

Best Time to Visit Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh

If you are looking for a serene experience in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh, it is important to understand the weather conditions for a great getaway. Surprisingly, unlike other valleys in India, Ziro experiences a cold climate throughout the year, making it a popular tourist destination.

Winter (September to February)

The best time to visit Ziro Valley is during the autumn months from September to October. The weather remains super cold and is ideal for a heavenly getaway. The temperature can drop to -13°C.

The snowy climate enables you to explore the beauty of the valley. Since it is the peak time, you can also expect a large amount of visitors to the landscapes of Ziro. It is also the time when you can be a part of interesting fairs and festivals.

Summer (April to May)

If you are looking for a relaxing atmosphere with minimal crowds, you can opt for the shoulder season. The second-best time to visit Ziro Valley is between the months of March and May.

The region experiences moderate temperatures ranging from -1°C to 15°C. It is the time to witness floral beauty, wild animals and lush greenery. You can definitely opt for cultural experiences as the valley is not very crowded.

Monsoon (July to August)

The monsoon in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh, invites unpredictable weather. It can start raining heavily anytime, and the temperature can drop to extremes.

It is also the time when you can witness cascading waterfalls making their way through the valley. If you love adventure and would want to take advantage of low prices on hotels, this can be a good time for you! Be prepared for the changing weather conditions and thunderstorms.

Things to Know Before Visiting Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh is located close to the border; hence, you need an Inner Line Permit (ILP) to enter the state. You can easily get from the offices in Itanagar, Delhi, or Guwahati.

- Ziro is home to the Apatani tribes, who are known for facial tattoos. So, respect the local customs, rituals and their everyday lifestyle.

- Always ask for permission before capturing the pictures of people around.

- Attend the Ziro Music Festival characterised by the fusion of artists, musicians and music enthusiasts from all over the globe!

- It is best to dress modestly in temples and across the valley.

- Know that local cuisine is limited, with most restaurants serving the same dish. You shall find bamboo shoots, rice, millets, smoked pork and apong (rice beer). It is best to carry snacks and food items if you prefer certain foods.

- It is a remote destination if you visit the hillside. So, carry medicines and toiletries to avoid any hassle.

- Ziro believes in sustainable tourism, so do not litter the area and be mindful of your actions.

- Carry enough warm clothes, no matter the season. The destination experiences cooler nights on most days.

Serenity Awaits Your Presence!

Ziro Valley in Arunachal is no less than a heavenly destination you imagine after reading a fairy tale. Abundant lush greenery, snow-capped peaks and tribal settlements make it a place of solace and wonder. What better than living a simplistic life where you wander through the valley, enjoy subtle meals and discover the true joys of life?

However hard you try, such experiences are only available in rural tourism initiatives by the government. As these places capture the essence of nature, you honestly get an opportunity to unwind and rejuvenate. It is the jaw-dropping beauty of a place that turns every traveller into an artist, either capturing pictures or writing a book amidst the hills.