Nestled in the foothills of the Eastern Ghats, millions of pilgrims from across the world visit the Sri Venkateswara Temple at Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. Tirupati’s spiritual atmosphere is unquestionably alluring. The area also provides a treasure trove of undiscovered natural beauty, historical sites, cultural riches and several places to visit near Tirupati.

In order to make sure that your visit to Tirupati is not only spiritually rewarding but also a fascinating tour of the surrounding locations, in this article, we’ll talk about the places to visit near Tirupati, tourist places near Tirupati and shall reveal the hidden treasures and must-see locations.

Let’s delve deeper into the must-see places to visit near Tirupati

1. Tirumala

The revered pilgrimage site of Tirumala is the site of the widely respected Sri Venkateswara Temple and one of the most important places to visit near Tirupati. You will be greeted by breathtaking vistas of the lush foliage and tranquil surroundings as you ascend the winding roads that lead to this spiritual refuge.

The Sri Venkateswara Temple is a marvel of Dravidian architecture and a representation of devotion. As soon as you enter the complex of the temple, you will experience peace as you take in the grandeur of the divine and the artistic carvings that grace the walls.

Take a trekking expedition to discover the picturesque splendour of the mountains. You’ll be captivated by the verdant woods, tumbling waterfalls, and expansive views.

Explore the history and mythology related to the temple by going to the Sri Venkateswara Museum. The museum displays a unique assortment of artifacts, sculptures, and paintings that illustrate Lord Venkateswara’s legends and stories.

Enjoy the delicious prasadam, or offering, provided at the temple to round out your trip to Tirumala. Don’t forget to try the famed laddu, a sweet treat that has a connection with Tirumala.

2. Srikalahasti

Srikalahasti ought to be on your list of places to visit near Tirupati within 50 kms. This is one of the oldest and most revered Shiva Kshetras in Chittoor district, Andhra Pradesh. The Srikalahasteeswara Temple, which was erected in the 10th century and carved out of the side of a sizable stone hill, is what makes Srikalahasti notable.

The temple is situated along the banks of the River Swarnamukhi, an important river in South India and a tributary of the River Pennar. The 3 ancient epics, the Skanda Purana, Shiva Purana, and Linga Purana, all make mention of the historic Shiva temple at Srikalahasti, which makes this

one of the holiest places to visit near Tirupati.

According to the Skanda Purana, Arjuna saw Rishi Bharadwaja on a hilltop while visiting this location to worship Kalahasteeswara, also known as Lord Shiva. Over the main gate of this temple is a massive, historic gopuram that towers 120 feet tall.

The closest airport, Renigunta, offers direct flights from Delhi, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Bangalore. The railway station in Kalahasti has good connections. From Srikalahasti, buses go to the nearby cities.

3. Kanipakam

The Varasiddhi Vinayaka Temple in Kanipakam was constructed several centuries ago during the reign of the Vijayanagar Empire.

3 brothers dug a new well after theirs dried up, but when they reached a certain level and couldn’t dig any farther, they were stuck. The iron spade struck a stone that started to drip blood when they dug harder! The brothers shed their abnormalities as soon as the blood began to flow. The shocked locals tried to drill further down the well to investigate the source of the blood. The idol of Lord Ganesha, known as Varasiddhi Vinayaka, which literally translates to one who grants wishes, finally emerged from the water.

Only a small section of the idol was visible for a long time, and all efforts to dig further were fruitless. But as time passed, more and more of the idol was displayed. However, it is said that there still is some part of the idol in the well, and water may be seen in the main shrine.

This is another one of the most important places to visit near Tirupati within 100 km. Kanipakkam is located 165 kilometres from Chennai and 75 km from Tirupati. Between Tirupati to Kanipakkam, regular buses are operated by the government.

4. Chandragiri

Chandragiri is perhaps the most visited fort in Andhra Pradesh since it is frequently visited by those travelling to Tirupati. The citadel, which covers a total area of 25 acres, is divided into the Lower Fort and the Upper Fort. Due to its roughly crescent-shaped design, Chandragiri—which means “hill of the moon”—was bestowed.

It is believed that Immadi Narasinga Yadavaraya, who reigned from Narayanavanam, built the stronghold about 1000 CE. Yadavaraya dominion ended in 1376 with the Vijayanagara dynasty’s conquest. The closest airport to Chandragiri Fort is Tirupati. Chandragiri is well-connected and has frequent buses to and from other significant cities in the country.

5. Pulicat Lake & Sanctuary

One of the best tourist places near Tirupati is the Pulicat Lake Bird Sanctuary. The Pulicat, which has a total size of 720 square kilometres, is well-known among ornithologists and bird watchers. This is the second-largest brackish water ecosystem in India, with Orissa’s Chilika being the first one. The location is pleasant for travellers.

The town of Pulicat lies next to this lagoon created by the Bay of Bengal. Winters in the sanctuary are home to migratory birds from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. During the winter, the sanctuary attracts up to 15,000 flamingos.

6. Thiruttani

The birthplace of the late Dr. Sarvapalli Radha Krishnan, the first President of India, and the fifth abode of Lord Muruga are Tiruttani’s two main claims to fame.

The Sri Subramanyaswamy Temple, the main draw, attracts numerous visitors from all across the nation throughout the year. Private automobiles, auto-rickshaws, public transportation buses and commercial mini-buses may all be used to get about Tiruttani. There are 365 stairs going to the shrine at the temple, which is perched on a tiny hill and symbolises the number of days in a year. You may try delectable South Indian vegetarian cuisine given as ‘prasadam’ or holy blessed food for worshippers at shockingly low costs just outside the temple.

7. Chittoor

Chittoor is a famous and revered city in Andhra Pradesh that is situated on the banks of the Ponnai River. The most respected pilgrimage destination in the nation, Tirupathi Balaji in Tirumala, draws visitors from all over the country and the world to Chittoor throughout the year.

The best jaggery in India is produced at Chittoor, which is also referred to as the Mango City since it sells a wide variety of mangoes all summer long. The best times to visit Chittoor are during the monsoon and the winter. Since Chittoor lacks a local airport, the majority of visitors arrive there via Tirupati. One of the greatest ways to see Chittoor is by taking a local city bus.

8. Vellore

The picturesque city of Vellore, sometimes referred to as the “Fort City,” is home to several historical landmarks and sacred locations. The Pallavas, the Cholas, the Carnatic Empire, and the Vijayanagar Kingdom, among other strong dynasties, previously ruled the city.

The Vellore fort was constructed by the Vijayanagara Kings and afterwards housed a number of dynasties, including the British, Marathas, Carnatic Nawabs, and Bijapur Sultans. The magnificent Golden Temple, which is dedicated to Goddess Mahalakshmi, is another important site in Vellore. The city is accessible throughout the entire year. There are hotels that range in price from low cost to luxurious.

9. Chennai

Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu and the fourth-largest city in India, is situated off the Bay of Bengal coast. Travel to Chennai, once known as Madras, to see the distinctive collection of British Raj-era architecture, serene pilgrimage sites, and mouthwatering South Indian food. Visitors may begin their day by taking a stroll along Chennai’s stunning Marina Beach, which is lined with impromptu markets and fishing boats. Start your exploration of Chennai’s other attractions with a trip to Mylapore, a charming district home to the energetic Kapaleeshwarar Temple. Then head to Rajaji Salai’s Fort in St George which was once home to the British East India Company.

A popular sight is the Government Museum, which is located inside the massive colonial-era Pantheon complex. Bronze artefacts from the Pallava period in the seventh century are displayed throughout the state museum. Among the most popular activities in Chennai city include surfing on the Covelong beach and exploring the crowded bazaars of George Town. Don’t leave without purchasing a genuine South Indian thali from the renowned Saravana Bhavan!

When you are in Tirupati and visiting the best places in Tirupati, you must check out these 10 best restaurants in Tirupati.

10. Nagalapuram

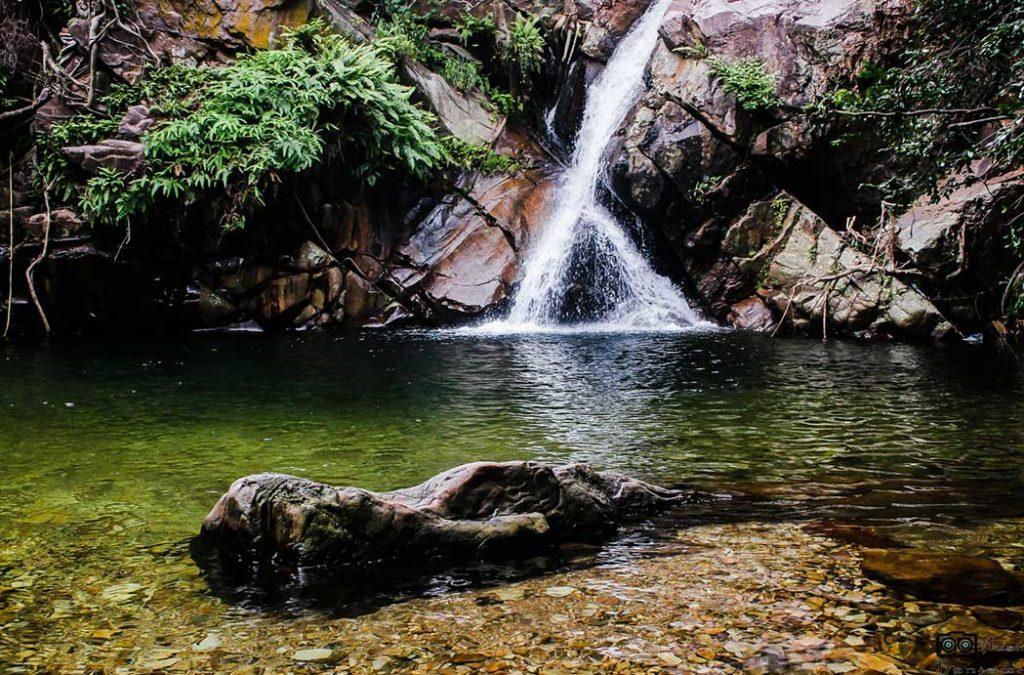

At an elevation of 213 feet, Nagalapuram is well-known for its Vedanarayana Temple and Vaishnavite shrine in the shape of Matsya, Lord Vishnu’s very first incarnation. As a result of its natural beauty and challenging slopes, Nagalapuram has, over time, gained popularity among trekkers and tourists alike.

Its enduring beauty draws visitors from throughout the nation, making this location a popular destination for hikers, campers, and photographers. The months of November through the end of March are the ideal times to visit Nagalapuram. You may take a taxi from the airport to Nagalapuram if you’re flying into Chennai. There are no trains that go from Chennai to Nagalapuram directly. Nagalapuram is easily accessible by road.

If you want more information about places to visit near Tirupati, do take a look here.

Looking for a temple tour of India? Take a look at this exhaustive list of the most prominent and famous temples of India.

In Conclusion

So there you have it, folks! When looking for places to visit near Tirupati or tourist places near Tirupati, the above-mentioned locations should serve as the ultimate guide to ensure you have one of the most wonderful getaways of your life. Good luck and happy travels!!