Did you know that Patna is one of the world’s oldest inhabited cities? The city’s origin can be traced back to the 5th century and it remained the capital of several empires, including the Maurya and Gupta. Its great heritage is still kept safe in the museums in Patna, which offer an in-depth view of not only Patna’s history and culture but also its innovative scientific discoveries. The museums in the city feature ancient artefacts, the Didarganj Yakshi statue, coins and much more which take us back in time to Bihar’s rich heritage.

Visit 8 Museums in Patna for Relics and Interactive Science Displays.

1. Patna Museum (Jadu Ghar)

Known as the gateway to Bihar’s rich heritage, the Patna Museum (Jadu Ghar) is one of the country’s oldest museums established in 1917 during British rule. The museum’s domes, central Chattri and traditional Jharokhas representing Indo-Saracenic architectural style bring history to life. The museum was first established in one of the Patna High Court’s rooms before the land was allocated for its construction in 1925. The new building designed by Rai Bahadur Vishnu Swarup was completed in 1928 and was opened to the public by Sir Hugh Lansdown Stephenson, the then Governor of Bihar and Orissa in 1929. The grandeur of the museum makes it one of the best places to visit in Patna.

Home to the Relics Casket of Buddha, the longest fossil tree in India, measuring 53 feet, Patna Museum, one of the remarkable museums in Patna has preserved important elements of history and culture. With over 75,000 antiquities, 4,000 terracotta and stone sculptures and 28,000 coins, the museum has a wide range of archaeological relics, paintings, textiles and sculptures from various eras like the Mauryan and British times.

Galleries: The National History Gallery, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Gallery and Geological Gallery.

Entry Fee: INR 15 for Indians | INR 250 for Foreigners.

Timing: 10:30 AM to 4:30 PM (Closed on Monday).

Location: Buddh Marg, Veerchand Patel Road Area, Patna, Bihar, 800001.

2. Bihar Museum

Designed by Japan’s Maki and associates in collaboration with Mumbai-based Opolis, the Bihar Museum, one of the popular museums in Patna, was established in 2015 as a modern cultural centre. The museum is located in the heart of Patna and is spread across 24,000 sq. mts. You can witness Bihar’s rich culture and historic legacy through innovative exhibitions and events in four distinct galleries which display Bihar’s journey from ancient Patalipautra to the 18th century and Bihari diaspora through historic regional contemporary artworks. The museum has preserved over 5,000 years of Bihar’s history, culture and art, fostering a sense of pride. The state’s historic legacy further makes it one of the popular places to visit in Bihar, not only for heritage enthusiasts but also for tourists worldwide.

The museum’s top attractions include the Didarganj Yakshi statue in Terracotta, artefacts from the Maurya coins, stone and bronze sculptures, thangkas and miniature paintings.

Galleries: Orientation Gallery, History Galleries and Special Galleries.

Entry Fee: INR 100 for Indians | INR 500 for Foreigners.

Timing: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM (Closed on Monday).

Location: Jawaharlal Nehru Marg, Veerchand Patel Road Area, Bailey Rd, Patna, Bihar, 800001.

Book Budget Hotels in Patna

3. Jalan Museum (Quila House)

Have you ever heard about a plate that changes colour or cracks if poisonous food is served on it? If not, then you need to visit the Jalan Museum to learn about such interesting facts. A remarkable representation of the English and Dutch architectural styles, the Jalan Museum (Quila House), was built in 1919. A prominent businessman and avid art collector, Diwan Bahadur Radha Krishna Jalan (R.K. Jalan) acquired the building through European auction houses. Although the house is still the private residence of the Jalan family, the ground floor of the building serves as the museum open to visitors for a limited time every day. So, on your visit to Patna, do not forget to visit this unique residence cum museum.

As one of the significant museums in Patna, Jalan Museum is home to over 10,000 interesting artefacts including a cutlery cabinet custom-made for King Henry II of France, a four-poster bed of Napoleon III, an ivory palanquin of Tipu Sultan, a dinner set of King George III, 200-year-old Persian rugs, Chinese jade dating back to 200 BC, Mughal filigree and 7th-century Chinese idols.

Entry Fee: No entry Fee.

Timing: 9:00 AM to 11:30 PM (Monday to Saturday) | 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM and 3:00 PM to 6:00 PM (Sunday).

Location: Quila Rd, Hajiganj, Patna, Bihar, 800008.

4. Sri Krishna Science Centre

If you think museums are just the display of historic artefacts, then you need to visit Sri Krishna Science Centre, the first regional science centre in India, built in 1978. This prominent hub for science education through engaging and interactive methods was named after Bihar’s first Chief Minister, Shri Krishna Singh. As a key regional unit of the National Council of Science Museums (NCSM) under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, the centre offers self-learning experiences that make learning enjoyable and accessible to visitors of all ages. The interactive approach and innovative facilities make it one of the most popular museums in Patna.

The museum has some of the most important artefacts including India’s first Hindi typewriter showcasing the evolution of technology, a digital planetarium offering immersive journeys through the cosmos, a 3D theatre and the Science on a Sphere (SOS) Theatre which provides innovative ways to visualize scientific concepts and a vibrant science park especially popular among children for its interactive displays.

Galleries: Its permanent galleries house participatory exhibits on various scientific themes, making it an enriching educational space.

Entry Fee: INR 25 for Adults | INR 15 for Children.

Timing: 10:00 AM to 6:30 PM (Monday to Sunday).

Location: West Gandhi Maidan, Raja Ji Salai, Lodipur, Patna, Bihar, 800001.

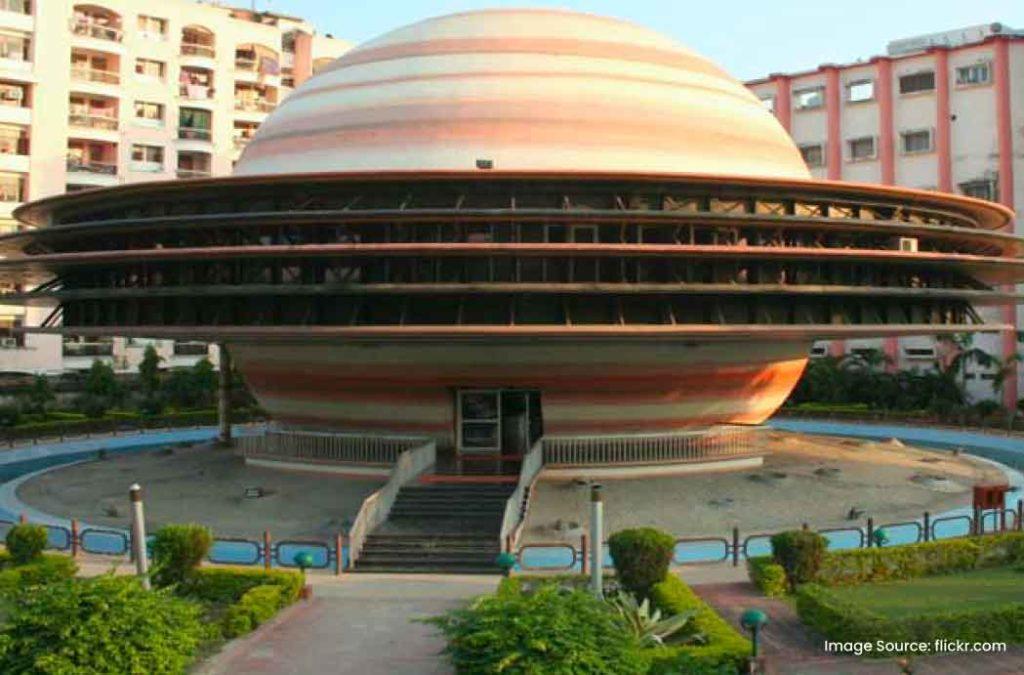

5. Patna Planetarium (Indira Gandhi Planetarium)

If you are interested in astronomy, then the Indira Gandhi Planetarium is one of the must-visit museums in Patna. Also known as the Taramandal “group of stars”, it is one of Asia’s oldest and largest planetariums. Its unique design resembling the planet Saturn, itself makes it a unique tourist attraction with captivating and immersive experiences.

The planetarium presents an innovative blend of education and entertainment for people belonging to all age groups, be it a well-maintained infrastructure, a modern projection system and dome-shaped screen or an engaging program. Exhibitions, seminars, workshops and conferences for astronomical learning and discourse provide insights into the grandeur of the cosmos.

Entry Fee: INR 50 (For age 3 years and above) | INR 10 per ticket concession for booking of full show by schools & educational institutions.

Timing:10:00 AM to 6:00 PM (Monday to Sunday).

Location: Jawaharlal Nehru Marg, Adalatganj, Kidwaipuri, Patna, Bihar, 800001.

6. Kumhrar Museum

The archaeological site and Kumhrar Museum take you through a journey of Mauryan civilisation, particularly the reign of Emperor Ashoka. The beautiful relics unearthed contribute to the art, culture and governance of the time. As you walk through the museum, the peaceful ambience, intriguing sculptures, pottery and inscriptions are astounding offering a harmonious experience of reliving history.

The architecture of the museum itself is beautifully designed and curated, showcasing the grandeur of the era. The Assembly Hall stands tall due to 80 pillars. This again represents the ancient city of Pataliputra in an exemplary manner. Sculptures, terracotta figurines, beads, pottery and inscriptions regarding the Mauryan civilization are present at the museum, making it one of the most popular museums in Patna.

Entry Fee: INR 15 for Indians | INR 250 for Foreigners.

Timing: 24 hours open.

Location: H5XM+WM6, Patna, Kumhrar, Bihar, 800026.

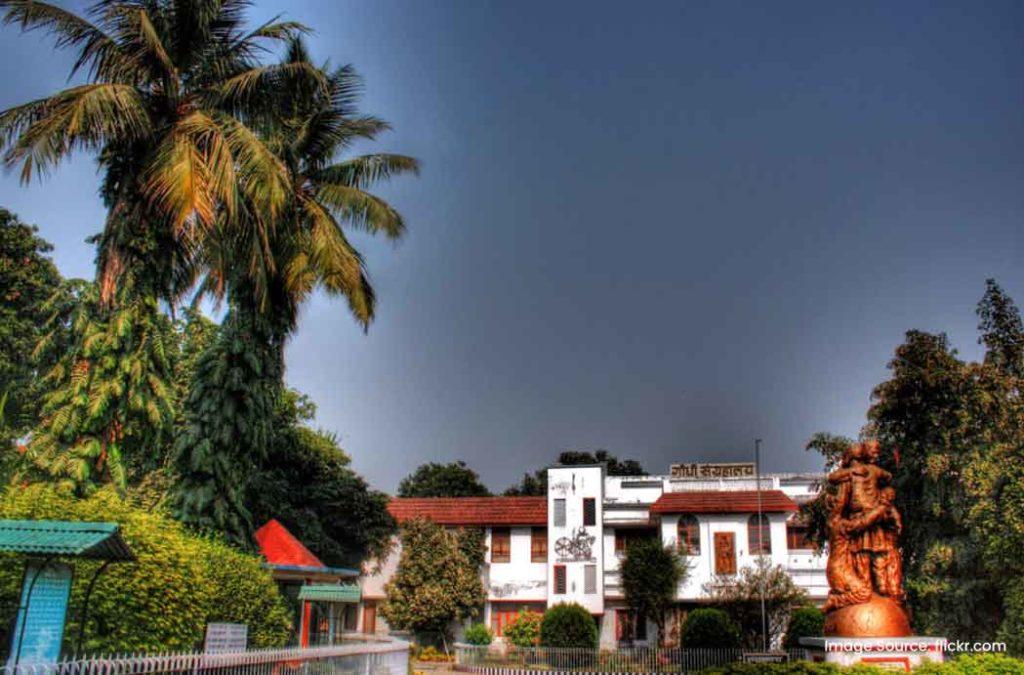

7. Gandhi Sangrahalaya

Gandhi Sangrahalaya is a museum established in 1967 in Patna, continuing the legacy and message of Mahatma Gandhi, Father of the Nation. After his assassination in 1948, leaders initiated the Gandhi Memorial Trust to continue his life and mission. The museum originally had photographs and other relevant items about the life of Gandhiji in some small rooms of an old building. The present museum formally inaugurated its first gallery on 16th December 1967. The exhibitions comprise pictorial accounts of significant events, the model of the room Gandhiji inhabited and other photographs, especially the rarest one encompassing the post-cremation photoshoot.

An audiovisual biography of Mahatma Gandhi containing photographs, manuscripts and works of art show major milestones throughout his life. This makes it one of the famous museums in Patna to add to your itinerary.

Auditoriums: The Kasturba Gandhi Hall and the Badshah Khan Hall are intended for cultural and educational performances. There are film screenings, seminars and exhibitions focused on contemporary issues and Gandhi’s teachings, ensuring his philosophy remains relevant to modern times.

Entry Fee: Free

Timing: 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM (Closed on Saturday).

Location: North-West Gandhi Maidan, Ashok Raj Path, Patna Bihar, 800001.

8. Srikrishna Memorial Hall Museum

If you are looking forward to experiencing the vibrant culture and intellectual spirit of Patna, then you must visit one of the remarkable museums in Patna, Shrikrishna Memorial Hall. This is the second-largest auditorium in Bihar and was built as a multipurpose arena and convention centre during the 1970s. The centre is also named after the first chief minister of Bihar. This centre is a major attraction in the city for its central location, modern architecture and seating capacity of 2,000 people.

Exhibitions, conventions, trade shows, concert performances, conferences and political meetings are some of the events organised at the hall.

Entry Fee: INR 20 for Adults |INR 10 for Children Below 10 years | INR 5 for Students with ID.

Timing: 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM. It remains closed on Sundays and public holidays.

Location: Kargil Chowk, Gandhi Maidan Road, Near Gandhi Maidan, Patna, Bihar 800001.

Museums in Patna offer a glimpse of our rich past and innovative future. From heritage buildings to planetariums, there is plenty for every traveller. So, do visit these museums on your next trip to the city and enjoy a memorable experience of travelling back in time through various artefacts. Whether you are visiting the city for business or leisure, you can easily find restaurants in Patna for a delicious culinary experience. Moreover, the hotels in Patna near the tourist attractions are perfect for a comfortable and affordable stay.