A desert is a place on which can take you to a different world altogether. For people living in cities where greenery, people and buildings are not hard to find, deserts with sand dunes and camels are a very new and different experience. India is one of the countries lucky enough to have the Thar Desert, home to the alluring state of Rajasthan. The difference in atmosphere, people, terrain, flora and fauna is so visible that one gets easily astonished at the splendid beauty of the state.

One such little town is Jaisalmer, situated around 600kms from the state capital Jaipur. This city, also known as the ‘Golden City’ has the status of a World Heritage Site. And rightly so, because Jaisalmer speaks of thousands of years of history and culture that are hard to miss. If you are planning to visit this beautiful town, here is a list of 9 best places to visit in Jaisalmer that will make those plans final!

9 Popular Tourist Places to Visit in Jaisalmer on your next Trip

Jaisalmer is mostly famous for its forts because of the long history of the town, but you can also find adventure enthusiasts seeking an adrenaline rush heading to this city. Listed here are famous places in Jaisalmer that that will make your trip to the town a memorable one.

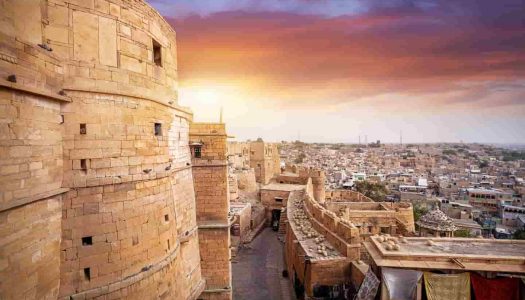

1. Jaisalmer Fort

This fort was built in 1156 AD by the Rajput King, Rawal Jaisal. The fort was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO back in 2013. It has unique architecture and is built by bulky sandstones.

The fort was primarily built to provide refuge to travellers making their way through the Silk Route which was the biggest trade route in the world back then. If you are a history, culture and architectural enthusiast, then this fort is a must-visit spot among the famous places to see in Jaisalmer.

2. Desert Culture Centre and Museum

Jaisalmer is a city of museums, and the Desert Culture Centre and Museum is the best of them all. This museum offers an enlightening peek into the long history of Rajasthan and Jaisalmer City.

From folk music to dance, cuisine, infrastructure, animals, fauna, and rulers who ruled long ago, this museum will tell you more about Rajasthan than any other museum. The ancient paintings and colourful attires take us back to the past to experience real Rajasthan. A recommended visit, this is among the top places to see in Jaisalmer.

3. The Gadi Sagar

The Gadi Sagar Lake is an artificial water body which was built way back in 1367. It was built as a water reservoir and acted as a breath of fresh air in the desert. It was the sole source of water for Jaisalmer at one point. The lake is surrounded by temples, and the steps that lead to the water were constructed years later.

The lake has a very interesting story behind the beautiful Tilon Gate which serves as the entrance to the lake. Unravel this story with a visit to this beautiful water body which is one of the most famous tourist attractions in Jaisalmer.

4. Lodharva

Lodharva is a small village around 15 km from Jaisalmer which is a beauty forgotten in the pages of History. Once the capital of the Bhatti Empire, the city was ransacked many times, which forced Rajput King Rawal Jaisal to shift his capital to another town, later known as Jaisalmer.

This village is famous for its Jain Temple which reminds one of peace on earth. Even though this place is visited by tourists every year, it remains, like before, deserted. The infrastructure, ambience and serenity of the temple are calming.

5. Sam Sand Dunes

Sam Sand Dunes are famous for their camel safaris. A common tourist attraction, it is a must- try in Jaisalmer. The best time to go for a Camel Safari in Sam Sand Dunes is between 4-6 am before sunrise or 4-6 pm before sunset. You can enjoy the beauty of desert while on a camel ride and the soft sand is hard to miss.

6. Thar Heritage Museum

This is one unique museum that is based only on the Thar Desert. Know how what was once a sea turned into a desert by visiting this historic museum. It presents ancient manuscripts, Jaisalmer coins, Sea fossils and ornaments of camels which make it one of the best places to visit in Jaisalmer.

7. Patwon Ki Haveli

Patwon Ki Haveli is an insight to the brilliance of architectural design back in the days. It gives us a chance to glimpse into how people lived back in the day. This Haveli, though, has no royal significance but has beautiful scriptures and elements of a Haveli which make it of great cultural importance.

8. Desert National Park

One of the largest National Parks in India, this Park offers the best look inside the environment of the Thar Desert. Though the park does not have many terrestrials but has a very rich bird life. These include Eagles, Vultures, Buzzards and Falcons. A very rare species, The Great Indian Bustard is also found at this park.

9. Adventure Sports

Jaisalmer apart from having historic significance is also a major tourist attraction for adventure lovers. Because it is in a terrain where you will find nowhere else in India, it has given birth to a horde of adventures like Parasailing, Jeep Safari, Quad Biking, Para Motoring, Hot Air Balloon ride, Dune Bashing, etc.

Jaisalmer is the heart of Rajasthan with rich culture and history. The Forts and Havelis at this small town present a once-in-a-lifetime experience and a glimpse of the past. The desert experience takes you to a very different world, and the beauty of Jaisalmer city is to die for. After you are done exploring these beautiful places to visit in Jaisalmer, do tell us which ones do you like the most!